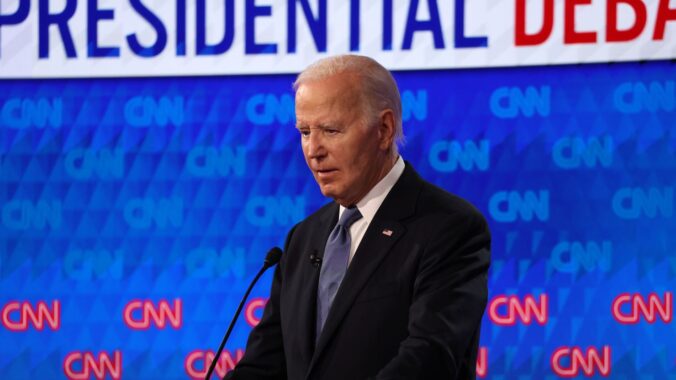

The world is keenly focused on our aging president and debating his mental capacity to properly execute the duties of the office. This debate is not new. At least three former presidents of the 20th century also faced questions about their age and capacity to carry out their presidential duties, especially during their later years in office or while campaigning for re-election. Here are some notable examples:

Ronald Reagan:

Age at Inauguration: Reagan was 69 years old when he took office in 1981, making him the oldest president at the time.

Concerns: By his second term, Reagan faced scrutiny over his age and health. In 1984, during a debate with Walter Mondale, Reagan addressed concerns about his age with a well-received joke, saying he would not make age an issue by exploiting his opponent’s “youth and inexperience.” Later, in 1994, Reagan announced he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, leading to retrospective speculation about whether he had exhibited early signs of the disease while in office.

Dwight D. Eisenhower:

Age at Inauguration: Eisenhower was 62 when he took office in 1953.

Health Issues: Eisenhower suffered a heart attack in 1955, a stroke in 1957, and underwent surgery for Crohn’s disease in 1956. These health issues raised concerns about his ability to perform his presidential duties, though he continued to serve until the end of his second term in 1961.

Franklin D. Roosevelt:

Age at Fourth Inauguration: Roosevelt was 63 years old when he was inaugurated for his fourth term in 1945.

Health Issues: Roosevelt’s health had been a concern due to his polio and declining physical condition. During his later years, he was visibly frail, and his death in April 1945, just months into his fourth term, intensified scrutiny about his health during his presidency.

Normal Cognitive Decline vs. Cognitive Diseases

As people age, it’s common to experience a gradual decline in certain cognitive functions. This decline is usually mild and does not significantly interfere with daily life. Normal cognitive decline can manifest in several ways:

- Multitasking: The ability to juggle multiple tasks simultaneously tends to decrease with age. Older adults may find it more challenging to switch between tasks quickly and efficiently, often needing more time to complete activities that require divided attention.

- Executive Functions: These include skills such as planning, problem solving, and decision-making. Aging can affect the brain’s prefrontal cortex, leading to slower processing speeds and difficulties in managing complex tasks that require these higher order cognitive functions.

- Processing Speed: Older brains generally process information more slowly than younger ones. This can impact the ability to react quickly in situations requiring fast decision-making, such as driving or operating machinery.

In contrast, cognitive diseases involve more severe and progressive decline. Conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and various forms of dementia are characterized by substantial impairments in memory, thinking, and reasoning that interfere with daily activities and quality of life.

Impact on Daily Life and Professional Roles

The cognitive changes associated with normal aging can affect various aspects of daily life, from simple tasks to complex professional roles. For example, older adults might struggle with remembering appointments, managing finances, or learning new technologies. These challenges raise important questions about the capacity of older individuals to continue performing certain activities or holding specific positions, especially those requiring high levels of cognitive function and quick decision-making.

- Multitasking and Executive Functions: Professions that require the ability to multitask or execute complex plans, such as surgeons or air traffic controllers, might be particularly impacted by age-related cognitive decline. The decreased ability to handle multiple stimuli simultaneously and make quick, effective decisions can pose significant risks in these fields.

- Processing Speed: Occupations like piloting a commercial airliner demand quick reflexes and rapid information processing. Slower reaction times and decision-making capabilities in older pilots could potentially compromise safety. For this reason, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has set specific age regulations for commercial pilots, setting the mandatory retirement age for airline pilots at 65.

Ethical Delemmas

Determining whether normal age-related cognitive decline should restrict older individuals from certain roles or activities involves complex ethical considerations. On one hand, it’s essential to ensure public safety and maintain high standards in professions where cognitive performance is critical. On the other hand, imposing blanket restrictions based on age can be seen as discriminatory and fail to recognize the individual variability in cognitive aging.

- Balancing Safety and Fairness: One of the main ethical dilemmas is finding a balance between safety and fairness. It’s important to evaluate individuals based on their actual cognitive abilities rather than their age alone. Regular cognitive assessments and performance evaluations can help determine whether an older person is still capable of performing their duties effectively.

- Respecting Autonomy: Older adults have the right to make decisions about their lives, including their careers. Ensuring that they are treated with respect and given the opportunity to continue contributing to society is crucial. Any policies or practices should aim to support and accommodate older individuals rather than exclude them arbitrarily.

- Societal Impact: The aging population is growing, and older adults play an increasingly vital role in the workforce and community. Addressing the challenges posed by cognitive decline requires societal efforts to create supportive environments, provide adequate resources, and promote lifelong learning and cognitive health.

Implications of Aging on the Presidency

Beyond the constitutional and legal requirements, there are several capabilities, skills, and aptitudes implied as necessary for effectively carrying out the duties of the presidency, at least some of which can be affected by normal cognitive decline; however there are also adaptive measures that a president can use to mitigate the effect of aging on his or her skills.

- Leadership and Decision-Making: The president must possess strong leadership qualities and the ability to make critical decisions, often under pressure. This includes the capacity to guide the nation during crises and set strategic directions.

- Impact: Normal aging may slow down decision-making processes and reduce the ability to quickly process information and respond to crises. Cognitive decline can impair judgment and the ability to weigh complex variables effectively.

- Adaptation: A well-structured team of advisors and a robust decision-making framework can help mitigate these effects, ensuring decisions are still sound and timely.

- Diplomacy and Communication: Effective communication skills are vital for addressing the public, negotiating with foreign leaders, and working with Congress. Diplomatic acumen is necessary for managing international relations and representing the U.S. on the global stage.

- Impact: Aging can affect verbal fluency, making it harder to articulate thoughts clearly. Hearing loss and other sensory declines can also impact communication abilities.

- Adaptation: Using clear and concise communication tools, relying more on written communication, and ensuring supportive environments for important discussions can help maintain effective diplomacy.

Understanding of Government and Policy: A thorough understanding of the U.S. government, its functions, and the policy-making process is essential. This includes knowledge of domestic and foreign policy issues.

- Impact: Memory decline may affect the ability to recall detailed policy information or past decisions. Executive functions, including the ability to plan and organize complex information, can also decline.

- Adaptation: Regular briefings, detailed notes, and the support of knowledgeable aides can help an aging leader stay informed and organized.

Ethical Judgment and Integrity: The president is expected to uphold high ethical standards and demonstrate integrity in both personal conduct and official duties. This includes avoiding conflicts of interest and acting in the nation’s best interest.

- Impact: While ethical principles are generally stable, cognitive decline can affect complex decision-making and the ability to foresee the long-term consequences of actions.

- Adaptation: Relying on trusted advisors and maintaining transparency in decision-making processes can help uphold ethical standards.

Management and Delegation: The ability to manage a large executive branch and delegate responsibilities effectively is crucial. This includes appointing capable individuals to key positions and overseeing their performance.

- Impact: Aging can affect multitasking abilities and the speed of processing information, making it harder to manage a large team effectively.

- Adaptation: Delegating more responsibilities to trusted team members and focusing on high-level oversight rather than day-to-day management can help maintain effective leadership.

Problem-Solving and Adaptability: The president must be adept at problem-solving and adaptable to changing circumstances. This includes responding to unforeseen events and crises with appropriate strategies.

- Impact: Cognitive decline can reduce creativity and the ability to think outside the box, making it harder to develop innovative solutions to new problems.

- Adaptation: Encouraging a culture of collaborative problem-solving and seeking diverse perspectives can help compensate for any decline in individual problem-solving abilities.

Mental and Physical Stamina: The demands of the presidency require substantial mental and physical stamina. The ability to handle the stress and long hours associated with the role is critical.

- Impact: Aging naturally reduces physical stamina and can also affect mental endurance, making it harder to maintain the long hours and high-stress environment of the presidency.

- Adaptation: Ensuring a healthy work-life balance, regular health check-ups, and a supportive environment can help maintain stamina.

- Vision and Strategic Thinking: A clear vision for the country’s future and the ability to think strategically about long-term goals and challenges are important qualities for a president.

- Impact: Strategic thinking requires both a long-term perspective and the ability to synthesize complex information, both of which can be affected by cognitive decline.

- Adaptation: Regular strategic planning sessions with a diverse group of advisors can help maintain a clear and forward-looking vision.

Conclusion

Aging and cognitive decline are natural processes that affect everyone to varying degrees. While it’s essential to differentiate between normal age-related changes and cognitive diseases, it’s equally important to consider the ethical implications of restricting older individuals from certain roles or activities. Normal aging and cognitive decline can also impact the aptitudes and skills necessary for the presidency, necessitating various strategies and adaptations to help mitigate these effects. By leveraging the support of a capable team, utilizing clear communication tools, and maintaining a focus on health and well-being, an aging president can continue to perform their duties effectively.